Independent authors and revenue share

Today I got a pitch from an independent author about producing his book for Audible. He offered a 50/50 revenue share deal. The book has a very attractive, professional cover. It has a reasonable number of reviews on Amazon. As an author, he has published 12 other books in the same genre. But in the end, I turned down his offer to audition. Why?

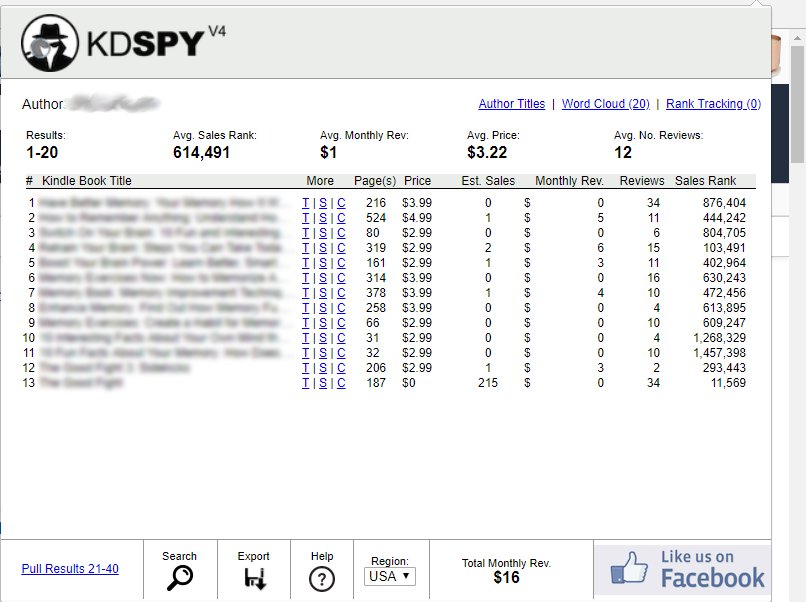

In a word, it came down to one thing: sales. His sales just aren’t enough to make his books a viable revenue-share agreement for an established audiobook narrator. And as audiobook producers, we’re not limited to educated guesses. We can use the same tools you have to check on rankings, sales, etc. So for example, I ran this guy’s library through Kindle Spy. (Names and details are blurred to protect his privacy.)

[pullquote class=”right” background-color=”#F0F8FF”]In a revenue share deal through ACX, the voice actor takes home 20% of net sales. Not gross, net.[/pullquote] Take a look. Now, I am not saying this is a bad guy. I certainly am not accusing him of bad faith. Maybe he just never thought about it from our side of things. But after 13 books in the same series, his sales last month were a grand total of $16. That is for all his books. The book he pitched to me sold an estimated zero copies. It is not a direct apples-to-apples comparison, because audiobooks sell separately from print books. Often the price is higher, and usually fewer audiobooks sell than print copies. Royalties are structured differently depending on whether the client buys the audiobook or listens as part of a monthly subscription. However, if his print books are not selling, how likely is it that his audiobooks will fare better? It would have been about three solid weeks of work with no assurance that I would make anything for the effort.

Revenue share is about making the actor more money

My dear independent author friends, it is time for straight talk about the revenue-share concept. In author forums I see a lot of comments from authors who seem to be confused about what revenue share is and is not meant to be. “No one will look at my revenue-share offer,” is a common complaint. “The auditions I get are low quality,” is another. These complaints are based on a basic misunderstanding of what the revenue-share model is meant to accomplish. Do you want to know what it is? The revenue-share model is meant to give the narrator the opportunity to make more from revenue share than he would from being paid up front. In the same way a movie actor like Tom Cruise or Julia Roberts might agree to take some of their pay in the form of royalties in the hopes of a long-term score, so an audiobook actor may consider a revenue-share agreement if they feel the book in question may make long-term, dynamite sales. This is why these deals are mostly done with established authors who have a built-in fan base that is eagerly awaiting every installment of a series. They often have vast mailing lists of superfans, as evidenced by strong pre-sales of their books.

Look, I get it. I’m an independent author too. So is my wife. Launching your book is expensive. Promotion is expensive. It’s hard to get people on your MailChimp list. Someone told you an audiobook is a great thing to add to your “funnel” and bring people in. Maybe you approached some actors about producing your book for Audible and went “yikes!” at the price. And then you heard about revenue share. Perhaps it occurred to you that this idea might be a way to test the waters with an audiobook while avoiding the risk of paying up front for the project.

But who is risking their time and energy when they make an audiobook on revenue share? That’s right, the narrator. And by the way, they have no control over what you do with it. How do you plan to market it? Are you planning to make it a perma-free? Have you stopped to consider what half of perma-free is worth? Did you know Amazon controls the price of revenue share books produced through the ACX platform? They set the price pretty high, which discourages readers from trying nobodies. There are other risks, too. For example, if you forget to file your tax paperwork, Amazon will take down the book I spent three weeks reading. If you look like you’re doing this as a hobby and not a business, it’s not a risk I can take.

What you are up against

When you open a casting call, you are competing with authors and publishers who are offering narrators $250 per finished hour (PFH) up [pullquote]Think of a “PFH” like a dozen eggs. It’s an industry measurement of units.[/pullquote] front or more. One PFH is about 9,000 to 9,300 words of your book, depending on the material. Each one of those finished hours costs your narrator between four to seven hours of work in real terms. And if you’re hiring a professional narrator, they’ll be hiring a professional of their own to proof and master their work before they send it to you. That is going to cost them a minimum of $40 PFH or more. Do the numbers pencil out for your narrator at 20% of your projected sales? If your book doesn’t sell, they’ll be investing their time plus $40 PFH or more of their own money for the pleasure of narrating your book!

As I wrote in my e-book The Insider’s Guide to Your Audiobook, before embarking on getting an audiobook made, it’s important to quantify why you want it and what it’s worth to you. That’s right, sketch it out in dollars and cents. Is this book worth the price of getting it made? If not, perhaps now is not the time to do it. Perhaps it makes more sense to put that money toward more paid promotion or a better cover. If you plan to use it as a perma-free funnel item, what is that worth to you? Run those numbers and budget accordingly.

What about the exceptions?

You’re right. Sometimes the stars can align perfectly. Sometimes there is this new author who has just one book out and it takes off. And sometimes there is a new audiobook narrator who just needs something, anything, on their resume. But this is not the reality most of the time. More commonly, if you are an independent author with low sales, putting your casting call out for revenue share will only guarantee that you receive scores of frustratingly low-quality auditions. They will probably be from new actors, perhaps with zero experience and poor equipment, or maybe radio guys who are trying to eke out a little cash. Could one of them turn out to be a diamond in the rough? Maybe. But there’s no guarantee.

The seven-year itch

One final consideration. Revenue-share schema vary from site to site, but a typical deal on ACX is a seven-year commitment. If you rush to grab the first narrator who agrees to do your book, what happens when your books actually start to sell? You can’t cancel the contract and have a more experienced narrator re-do the book! (That is, unless you can work a deal to buy your first narrator out.) So think it through carefully and calmly before you commit to a narrator.

There are lots of great reasons to have an audiobook made. But in audiobooks, as in life, there is no free lunch.

Dalan E. Decker is the owner of SoundFridge, an independent audio book production company.